Bizarre Belvidere: Exploring prehistoric Belvidere

COURTESY PHOTO Belvidere Republican

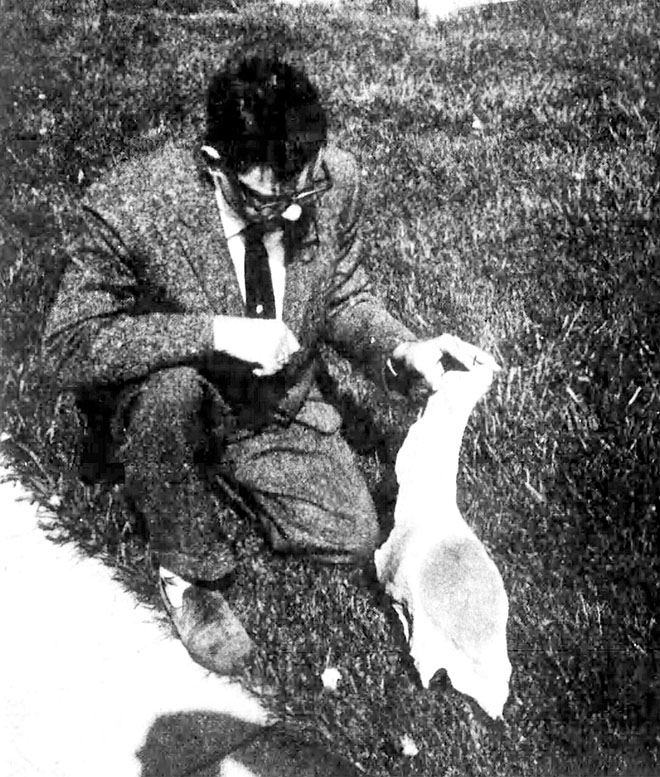

John Tripp is pictured with the first Belvidere mastodon bone.

Our third President, Thomas Jefferson, held a fascination with large, fossilized bones. Some historians go as far as to call him the “Father of Paleontology.” His home at Monticello housed a room referred to simply as “the bone room.” It held fragments of all manner of extinct, North American, creatures, but Jefferson was the most fascinated by two skeletons.

The first was a set of giant claw fossils that led him to believe a giant lion roamed the Americas. Jefferson called this creature the Megalonyx, literally meaning great claw. The name remains to this day, but paleontologists now believe this creature was a giant sloth.

His second obsession was what he believed to be a wooly mammoth but is now identified as a mastodon. Jefferson’s curiosity went so far that he even asked Lewis and Clark to determine if any mammoths were still alive during their expedition through the Louisiana Purchase Area.

While there were no living mammoths left in America, or anywhere, there were plenty of fossils. Mammoth bones had been found all across Illinois and the Midwest since Jefferson’s lifetime, but relatives of his most prized fossil, the mastodon, appeared to be absent from Illinois, the heart of Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase.

Remains had been found throughout Canada and the northern United States but never as far south as Illinois, at least not large bones. Small bone fragments had been found, but fragments are not taken as concrete evidence of local habitation. Their remains could have been trapped in a glacier and crushed over millennia of icy pressure. Ancient glaciers, like modern glaciers, are known to move and to melt.

These factors together make it possible to find bone fragments some distance from where an animal lived and died. Large fossils, less disturbed by the elements, would be better evidence that mastodons roamed our great plains.

This evidence was eventually found right here, in Belvidere. On May 12 1964, workers at a gravel pit off Appleton Road brought up sediment from a small quarry lake as usual. Within their hauls that day, they found three mysterious bones. The bones were turned over to John Tripp, of the Boone County Historical Society, who contacted Beloit College to identify them. Researchers at the college determined they were likely mastodon bones.

One of the bones was the kind of large fossil paleontologists had been searching for. The fossil was large and contained the ball of a femur attached to a chunk of the mastodon’s pelvis. Divers ventured to the bottom of the lake, hoping to find more bones, but were unsuccessful after two separate ventures.

The lack of a more complete skeleton meant that the Belvidere discovery alone could not prove mastodons roamed Illinois, but it served as early evidence for a case that would be built over the following years here and throughout the state.

In 1974, workers at another gravel company off Squaw Prairie Road found a large Mastodon tooth in another quarry lake. Once again, a full or partial skeleton was not found, but teeth are an important find for differentiating mastodon from mammoth remains. Mastodon molars have distinct points at their ridges, which are believed to have been for eating hard branches off trees. Mammoth teeth are flatter, likely for pulverizing grass and weeds.

Later, in 1978, an intact mastodon femur was found in Poplar Grove. This bone is still proudly held by the Boone County Museum of History. These discoveries, as well as partial skeletons found throughout the state, convinced paleontologists that mastodons lived and died here and did not travel as mere glacier dust.

Large fossil remains are obviously the most visually interesting, but Belvidere holds even more fossil life within its quarries. The quarry off Irene Road specifically has been a hotspot for small, fossilized shells. These fossils are believed to be from the Ordovician period, transpiring over 400 million years ago.

Trapped within the rock of this quarry are fossilized sea snail shells, cephalopods, corals and trilobites. These types of fossils aren’t exactly rare or groundbreaking, but they are historically interesting and make for nice souvenirs.

Lewis and Clark were not able to accomplish what Jefferson once dreamed. There were no mammoths or mastodons left for them to find. There were no giant lions or beavers either. Once upon a time though, tens of thousands of years ago, they did roam across America, not just in the timbers of The North, but here in Illinois too, and Belvidere played its part in proving it.