Main Street and the railroad

COURTESY PHOTO Belvidere Republican

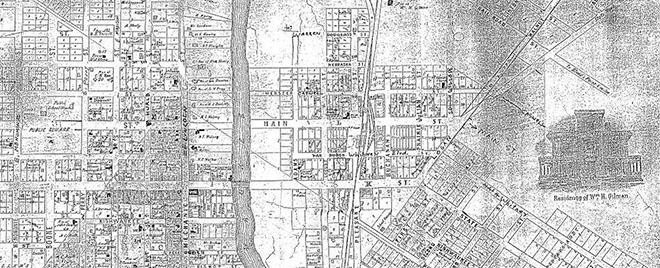

An 1856 map of Belvidere (North = left, South = right) shows the still complete Courthouse Square and William H. Gilman’s estate, “Gilman’s Forest.”

A main street is exactly what it sounds like—the main street for business in a populated area. So why, then, does our own Main Street play second fiddle to State Street or Logan?

Some might be quick to guess that it must be a modern development driven by access to the highway, and Main Street was the historic center of the city. That isn’t quite the case though.

In fact, Main Street’s short time in the limelight was over before mass-produced automobiles were even available for the public to purchase.

Belvidere’s pioneer citizens put great effort into planning the early layout of our city. At its founding, Belvidere was centered on two stagecoach roads. One was the State Road, which ran over what is now State Street, Logan Avenue, and Business 20. The other was the County Road, which is now Lincoln Avenue.

At the time though, it was called Mechanic Street. It was so named because “mechanics” could apply to be granted land there in exchange for developing the property. Back then, a mechanic was any tradesman who performed a hands-on skill: brick-laying, painting, masonry, etc. The State Road was meant to focus on business for travelers and Mechanic Street was meant to be the residential area.

Main Street crossed Mechanic to give residents easy access to what was supposed to be a “New England Style” town square, centering on the courthouse and crowded with walkable businesses. The street terminated at what is now Logan Avenue to bring in traffic from the State Road. The courthouse square itself actually cut off Main Street. There was no road between the courthouse and the park. Main Street didn’t open up across the courtyard until 1878, when it was clear the “New England Style” plan had fallen through.

The plan started to fall apart with the introduction of the railroad. This wasn’t a case of new technology throwing a wrench in old plans though. Negotiations for the railroad started as early as 1836, only a year or so after Belvidere’s formal incorporation.

Commissioning the railway was a complicated deal involving the state, railroad officials and representatives from the three major stops along the way from Chicago to Galena: Belvidere, Rockford and Freeport. Belvidere investors originally planned for the track to cross over the river and stop on the North Side of the city, near Courthouse Square.

However, William H Gilman, a major landowner in both Belvidere and Rockford, had other plans for the railway. He owned the lion’s share of the land south of the Kishwaukee River and east of the state road, and he knew that if he could encourage development on the south side of the river, he could make a fortune.

To accomplish this, he made an otherwise foolish offer to the railroad company. Gilman granted them right of way over his property, free of charge. Ebenezer Peck, a relative of Gilman, drew up the original railroad charter and held a lot of negotiating power with the company. Gilman’s offer and Peck’s influence proved enough to seal the deal.

Development continued around the courthouse for a few more years, but by the 1860s, business clearly favored the south side. This created a feud of sorts between Belvidere’s principle investors and politicians, preventing them from making joint investments in manufacturing.

Other Northern Illinois cities, Rockford, Freeport and Elgin, all had major manufacturing businesses some time before the National Sewing Machine Company came to town in 1886. A watch factory that eventually settled in Elgin was originally offered to Belvidere, but the deal fell through because northern and southern residents failed to pool their capital together.

An 1880 editorial in the Belvidere Republican had this to say about the difference between manufacturing in Belvidere and Rockford, “…the reason why Belvidere does not engage in manufacturing is from the lack of enterprise and capital. We don’t suppose there is much difference in the climate of the two towns; but there is a wide difference in the enterprise of the capitalists of Rockford and Belvidere.”

Even after the arrival of the National, manufacturing deals were still relatively slow. In 1895, a commentator from the Chicago Evening Journalexpressed their bewilderment at how few factories had opened in Belvidere despite its location and low cost of living. More industries did come over time but few had major stakeholders from Belvidere.

Even the Keene-Belvidere canning company, whose intimate relationship with local farms should have encouraged investment, was owned almost entirely by men from Freeport. This wouldn’t change until Hugh Funderberg took control many years later.

As generations changed, so did the feud. Shops and factories being on the south side of Belvidere and the north being residential wasn’t something to be upset about anymore. That was just the way Belvidere was.

Ironically, as highways came and commuter culture boomed, the whole thing became something of a moot issue. Nearby workplaces, walkable shops and a centralized courthouse were less of a priority than they were for our early citizens.

A main street that was hardly ever a main street is certainly bizarre. Even more bizarre, though, is just how much our city’s trajectory could be affected by a business disagreement. Gilman wasn’t some villain who only cared about himself. He lived in Belvidere and donated land for St. Joseph hospital. He did care for his community, and so did his northern rivals.

The most bizarre part of this story is that their civic duty couldn’t unite them.